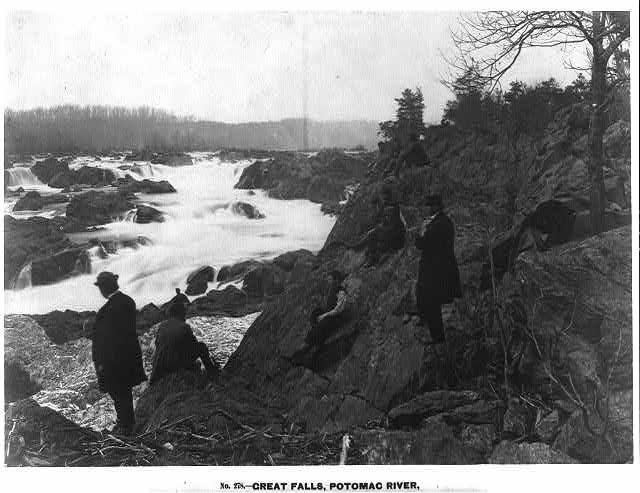

The Potomac River Gorge is considered one of the most spectacular and significant areas in the National Capitol Region. It is a geographical and environmental marvel; spanning 15 miles, the Gorge connects the Potomac’s freshwater to the first inklings of the Atlantic Ocean. It is home to over 1,400 plant species, many of them rare, as well as an abundance of wildlife. It holds a diverse geology that is world renowned, supports the highest concentration of rare plants in Maryland and hosts one of the deadliest stretches of whitewater east of the Mississippi. Yet, less than a mile from the concrete jungle of metropolitan D.C., the gorge has also served as a hub of transportation, exploration and human settlement for centuries.

The human co-mingling with such national—and specifically, natural—treasures, poses some important questions: How have areas like the Potomac River Gorge shaped and influenced our history and culture? How will a growing, modern civilization interact with such a diverse environment in ways that protect, preserve and celebrate its heritage? A two-year project conducted by UMD’s Historic Preservation Program is examining the important intersection of natural and cultural history, hoping to understand how they define our past and how they will shape our future.

The result of an ongoing partnership with the National Park Service – National Capitol Region (NPS-NCR), the Potomac Gorge project serves to provide the NPS with a beta test for a larger narrative of the intersection between environment and culture. Initially launched with Maryland’s Historic Preservation Program in 2013, the project is now in the hands of Faculty Research Associate Dr. Kirsten Crase. With the help of campus experts, Dr. Crase will develop a synthetic report outlining the entire human history of the area, in the hopes that the model can be replicated by the NPS in other parts of the country.

“The NPS selected the gorge simply because it’s such an amazing, diverse area,” said Kirsten. “It is steeped in history, both culturally and ecologically.”

Covering topics like transportation, trade history, plants and wildlife, the report is expansive. To keep the sheer scope of the project in a cohesive, digestible format, Crase will offer a “slice of life” of the Gorge, highlighting key, strategic points along the river, such as the C & O Canal, Clara Barton House, Glen Echo, the Georgetown waterfront and various other park areas. While she has an extensive bibliography of historic natural and cultural assets of the area, thanks to work completed by graduate students in the HISP program during the project’s first year, Crase is enlisting the help of environmental anthropologists and zoo archaeologists on campus to help with the nitty-gritty biological aspects. A GIS expert will also help create a “layering” of maps that will guide the analysis and reporting.

The macro and micro scale of the report, while not fully comprehensive, will offer many clues to understanding how the area’s resources intersect. More importantly, the report will help administrators understand how practices between the many organizations at work in the area interrelate.

“The Potomac River Gorge is a massive area, overlapping two states and the District of Columbia,” explained Crase. “There are many organizations at work in the Gorge; one part of the report will offer a better sense of how the various jurisdictions and management practices interrelate as well as identifying best practices for working together.”

An interim report will go through a roundtable review later this year by the campus team and several resource experts. Crase expects to complete the final report in 2016.

“I really enjoy the research; it’s incredibly exciting,” said Crase. “I find it fascinating how the Potomac is so intertwined throughout history, from the early Native Americans, through the Civil War, to modern society. It’s an excellent resource for this type of project.”