Many historians consider 1968 a turning point for the United States. Five years after the March on Washington and the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and four years after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, the country was in the throes of the Vietnam War when, in April, riots erupted nationwide in response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Of the 110 cities that endured riots, Washington, D.C., was hit especially hard, with the worst physical damage along 14th and 7th Streets, N.W. and H Street, N.E. The riots started at the intersection of 14th and U Streets, the center of what had been a vibrant, predominantly African American neighborhood for half a century. The social and economic blight that followed desegregation paved the way for the unrest and violence of 1968. Fast forward 50 years: the area around 14th and U is one of the most in-demand neighborhoods in the district and now experiencing extreme gentrification.

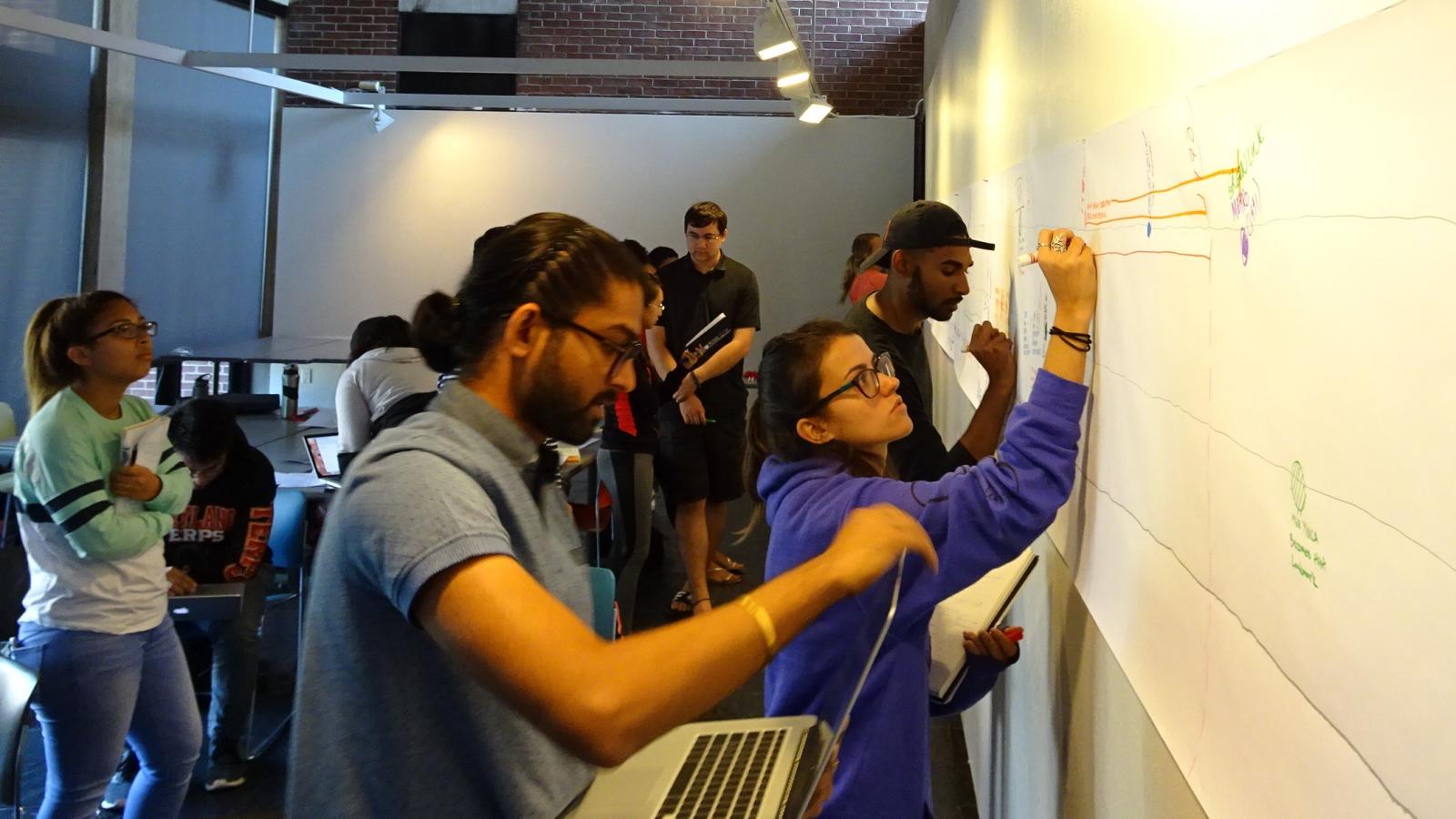

What drives the decline and resurgence of a neighborhood? A new project by graduate and undergraduate students in UMD’s Architecture Program explores the relationship between the built form, social and economic change and urban policy decisions. Part of Assistant Professor of Architecture Michele Lamprakos’ ARCH 478/678 course, Adaptation, the project looks at change over time at the corner of 14th and U Streets, N.W. and its surrounding neighborhood from the late 19th century to the present day, presenting interconnected stories of the area’s history: nodes or foci of community life; commercial and residential development; transportation and infrastructure; and social history/demographics. The graduate student team has conducted in-depth historical mapping, including the evolution of zoning. Combined, the project tells a compelling and revealing narrative about how architecture, the urban environment and social fabric interplay and influence change over time.

“This project provides a great opportunity for students to immerse themselves in the history of the neighborhood that was the focus of African-American cultural life and the center of the civil rights movement in D.C., and to understand how that history resonates today,” says Lamprakos. “I hope students have learned to see cities with new eyes.”

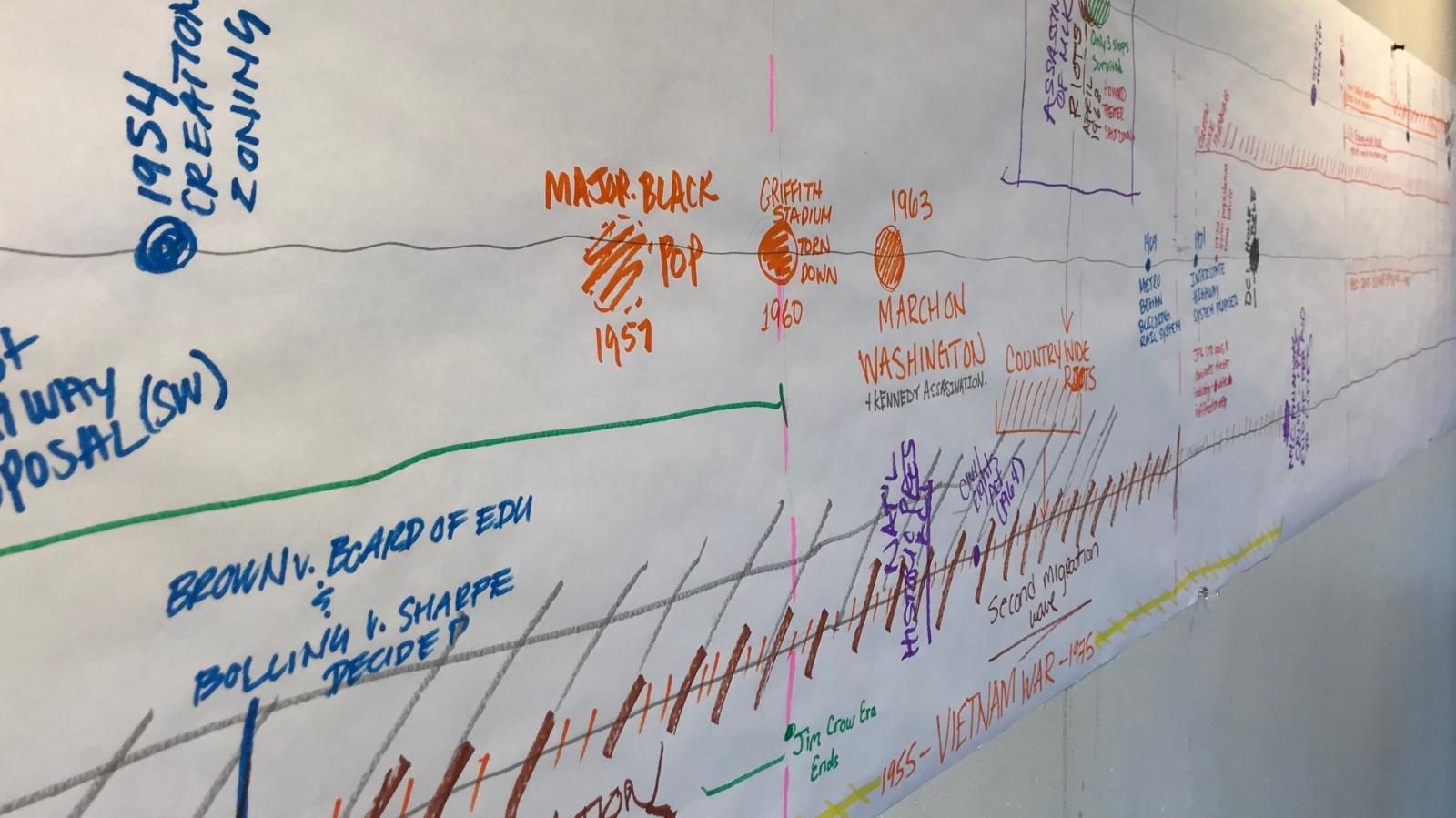

To begin this narrative, the students needed to gain historical context. Through assigned texts – like Blair Ruble’s Washington’s U Street: A Biography – research, site visits and guest lectures, students developed a timeline of social, economic and political events spanning from the late 19th century to present. Using maps and historic photographs, they developed a narrative about the ebb and flow of the neighborhood in response to a variety of instigators, including demographic shifts like the Great Migration; changing modes of transportation, in particular, the streetcar and the automobile; the decline of inner cities with suburbanization, white flight and (after desegregation) black flight; and the “back to the city” movement which has, since the 1990s, led to reinvestment and recovery, but also the displacement of long-time residents, businesses and institutions.

What was immediately clear to the students was how often these areas overlapped and interplayed within the bigger picture. The wax and wane of investment and types of investment, for instance, had direct results in the demographic make-up of the neighborhood.

“Each of our project areas faced the same historic events—segregation, urban decay, white flight—but combining them has helped us see the bigger picture,” said William Ayres, an undergraduate student working on the transportation narrative.

In addition to actual events, the students saw the impact of plans that never materialized—like the proposed Inner Loop (conceived in the late 1950s and not defeated until the late 1960s), which would have eviscerated the block between U and T Streets, N.W., including the entire study area. There were also “side effects” of beneficial capital projects, like WMATA’s Green Line. While the Green Line was considered a positive neighborhood addition on completion, cut-and-cover construction on U Street contributed to significant economic distress, restricting access and shuttering businesses. The improved access it brought to the area in the 1990s spurred frenzied transit-oriented development in the aughts, later contributing to neighborhood gentrification.

The students benefited greatly throughout the process from a neighborhood tour and lectures by David Haresign and Bill Bonstra (MAPP alumnus), architects who have worked on many projects along the 14th Street corridor. Other MAPP instructors lectured and served as guest critics – presenting a variety of perspectives on built and social form, from architecture, planning, historic preservation and real estate – and MAPP alumni Adam Chamy and Marques King, as well as university lecturer Georgeanne Matthews, facilitated a two-day charrette. UMD Libraries supported the work in various ways – the Architecture Library provided research support; Hornbake Library’s Special Collections provided large format atlases and other print sources; and the GIS/GeoSpatial Service Center developed maps that track demographic change.

“This project has made me more keenly aware of how designers can truly preserve or transform the meaning of a place,” said Emma Weber, a graduate architecture student. “It's not just some lines on a piece of paper; it's a costly apartment building that's raising prices of neighboring business ventures, it's the demolition of a jazz club that was a place of comfort during the worst of times. Or it can be a theater that preserves the history of the automobile showroom that once called its building home, hosting performances that celebrate the diverse neighborhood. It’s up to architects, engineers, and developers to be sensitive to the lives and culture that occupy a place.”

The interweaving stories cultivated by the students create a better understanding of the area’s rich and resilient history and how it is reflected in architecture and urban form. The U Street neighborhood was once considered a “city within a city,” where African Americans could enjoy entertainment, own businesses and develop a rich community prior to desegregation. Benefiting from the proximity of Howard University and transportation networks, 14th and U was by 1920 the intersection of two major poles, “Black Broadway” and “Auto Row.” It was the epicenter of many of the events surrounding the civil rights movement and—during the riots—offered safe places to meet, such as Ben’s Chili Bowl. It provides a historical example of community activism at large and small scales; neighborhood churches and activists were largely responsible for revitalization work around the U Street corridor and were early advocates for subsidized housing. It also provides powerful lessons in gentrification, disinvestment and how zoning and other policies can impact communities in large and subtle ways.

The community surrounding 14th and U Streets, N.W., is a community driven by racial solidarity and a determination to become self-sufficient at a time in history when the majority of its residents were denied basic human rights elsewhere,” said Aldana Caceres, an undergraduate student involved in the project. “U Street in the mid-1920s through the late 1940s is an exceptional demonstration of African-American resiliency at the height of segregation. Before this class, I had accepted the narrative, but I've learned that history is not always black and white. There is a story to this neighborhood that needs to be told and we have the responsibility to tell it.”

While only some of U Street’s history is reflected in the building facades – many of which have been protected thanks to the designation of two historic districts in the mid-1990s – the project has illustrated the area’s enduring resilience.

This is an extremely important class for architecture students, as it exposes students to the ideas of adaptive reuse and its impact on community planning” said undergraduate architecture student Ricky Fairhurst. “[Previous] classes that I've taken are about new buildings and new infrastructure which is great but, in reality, the biggest problem of the future will be to update what we already have. This course has really opened my eyes to architecture as a timekeeper of memories and past history. Our ideas, visions, technology and stories are all baked into the buildings we create. Much of that should be kept as a narrative of a building's own story.”

The student work will be on display as part of Rebirth: Fifty Years After the 1968 Martin Luther King Assassination Riots. This exhibition brings together the work of architects involved in the area’s revitalization and reflective projects by four area universities. The work will be open to the public at AIA’s DC headquarters March 26-May 26, with a project symposium on April 5. Learn more about how you can see the students’ work, here.