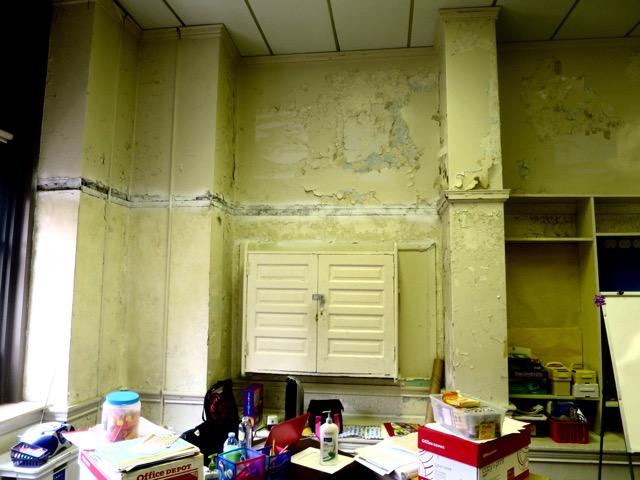

Squabbles this week over a $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure spending plan have generally skirted one of the messiest infrastructure failures in the United States: deteriorating public school buildings. A focal point for education and community, and a lifeline for many American families, they are also increasingly hazardous, said the University of Maryland’s Ariel Bierbaum, who has been studying the buildings in Philadelphia, from lead in the drinking water to exploding boilers.

As schools run a roughly $38 billion annual deficit just for building maintenance and upgrades, many advocates like Bierbaum argue public schools should be part of the federal infrastructure bill.

“In Philadelphia, like many districts, the response is a reactionary, kind of crisis mode,” said Bierbaum, an assistant professor of urban and community planning. “And the outcome is not good.”

Bierbaum has spent the past 15 years at the intersection of people, place and education, guided by a central question: How do we position school buildings as neighborhood assets? She spoke in an interview about the vicious cycle of broken schools, disparities in funding and who’s missing from the conversation.

Is Philadelphia an outlier, or is this a national crisis?

This is really an environmental justice issue. You have kids going to school in these buildings (that) are literally toxic and killing people. I would say that Philly is not an exceptional case—we see this across the country.

Right now, there are zero dollars that come out of the federal government to support school facility building or maintenance and management. It’s just not a thing that the education sector really takes seriously. A lot of districts just don’t have the capacity because they’re trained as great educators, not to understand capital asset management. This compounds existing health inequities for neighborhoods and families that are already disadvantaged.

How did it get to this point?

This situation in Philadelphia and in other communities is another imprint of larger geographic patterns of inequality in our country. The ways that metropolitan racial and socioeconomic segregation have cemented disadvantage are visible in the actual physical infrastructure of our school buildings.

This is a function of how we finance education, which is largely dependent on a community’s wealth. There are alarming disparities between low-wealth and high-wealth districts, and that often tracks along race and ethnic lines as well. A 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office report on school facilities found a gross percentage of schools—over half—with failing heating, ventilation or HVAC systems.

You advocate in a recent Philadelphia Inquirer op-ed for having families, teachers and school staff at the table in the planning process. Why is that important?

The people who live and work in these buildings eight to 12 hours a day have information that the district is either unable or uninterested in accessing. Currently it has no process set up to meaningfully engage parents, families or educators in questions surrounding school facilities management. We know from planning theory and practice that asset-based approaches work: Start at the strengths of the community, honor local knowledge and respect that the people closest to the issue know the most about their own experience. From there, we can create a framework and a process that guides policy decisions.

This fall, students from your urban planning class will take on this issue. What will they be doing?

The idea is to work with community and advocacy groups around schools in West Philadelphia on a pilot for developing what we call a people’s facilities master plan framework. Students will look at opportunities and constraints, conduct neighborhood analysis and engage in some best-practice case-study research on participatory processes specific to school planning so we can come up with some recommendations for boosting engagement around these highly technical issues of facilities management.

When we think about infrastructure in the traditional way, it’s usually through the purview of engineers; we don’t think about people. As planners, we have something to offer to expand our thinking about possibilities for change to mitigate harms and support resiliency.