Mount Rushmore casts a long shadow on the United States, and not because of its size. The chiseled monument to Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln was the result of an 1877 land grab from the Lakota Sioux of a sacred mountain range called the Black Hills or Six Grandfathers.

This semester, historic preservation graduate student Katherine Calvert wondered: Can the lost heritage of Mount Rushmore be reclaimed by elevating the rubble that its creation left behind?

Her project, part of the course “Destruction, Memory, Renewal,” imagines lights in the color of the Lakota medicine wheel—black, white, red and yellow—cast on the nearly 500,000 tons of rubble at the monument’s feet to illuminate the Black Hills’ destruction.

Michele Lamprakos, the architecture professor who teaches the course, challenged students to undertake a “monumental” task: propose an intervention at the site of a contested public statue, building or site. The project requirements prevent the structure from being removed, and any changes must be reversable. To grasp the intricate and shifting context of these monuments, students must dig deep into the monument’s “life,” researching the history, politics and public attitudes that drove the artists’ intentions and the subsequent culture shifts and events that changed its context and meaning.

“Why do monuments that for decades seem part of the everyday landscape spring to life at particular moments, provoking conflict, violence, defense?” she says. “The point is that they’re often erected decades after the event or person they commemorate. And they go on to outlive their makers.”

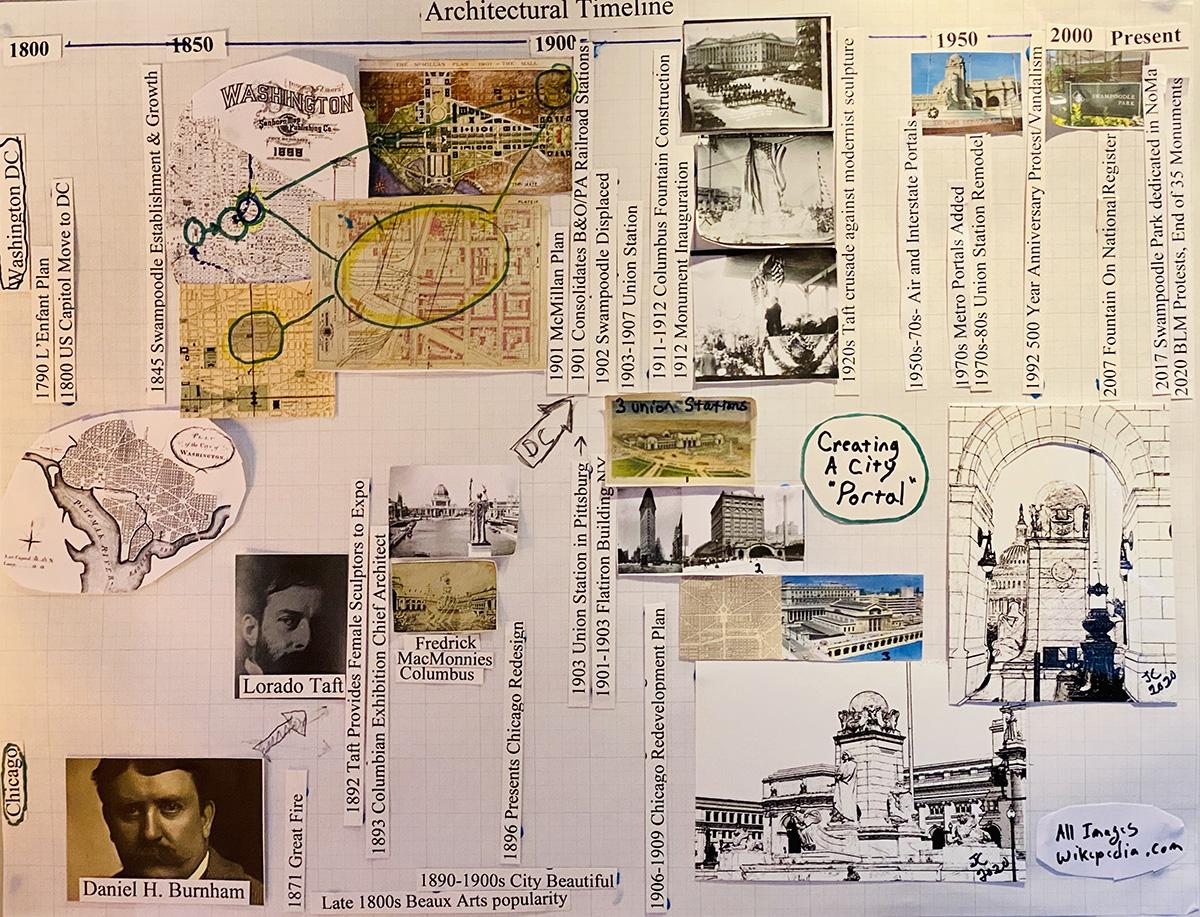

The project is part of a larger examination of the destruction and removal of monuments in the wake of an enormous global reckoning surrounding injustice and oppression, but also at times through instances of misinformation and raw iconoclasm. Central to class discussions are people, and how they experience places and spaces differently over time. Lamprakos asks students to approach the project, which spans the semester, as a way to broach difficult conversations and bring together divided communities. She trains students in a mixed method that includes historical research, timelines, map palimpsests and “thick description” in the form of writing and sketching.

“The students’ sites are very complex and globally connected,” said Lamprakos. “The synergy came, in part, from the fact that they’re from different disciplines: architecture, planning, historic preservation, art history and history. It’s a great example of what interdisciplinary research and collaboration can produce. And in a strange way, meeting online in the midst of the pandemic may have made the experience more intense.”

Lamprakos began offering “Destruction, Memory, Renewal” in 2017 to provide historical and theoretical context for destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East. But amid the recent wave of racial reckoning and divisive presidential election, both marked by protests and vandalism of controversial statues, Lamprakos redesigned the course project.

Calvert, who was reminded of the contention surrounding Rushmore after President Trump’s speech there this past summer, said, “I thought it would be an interesting challenge to work around something so big that it couldn’t be easily removed like a Confederate statue.”

Joel Carlson, who is pursuing a second master’s degree in history and museum scholarship, first saw the statue of Columbus outside Washington, D.C.’s Union Station on a walking tour about place and race in the city earlier this year. Erected in 1912 with great pomp and circumstance, the statue depicts old and new worlds through imperial iconography including a crouching Native American man. Over the past several decades, however, Columbus’ legacy has become increasingly controversial. Plans to remodel Union Station largely ignored the monument, which is now partially boarded up.

“It was right around the time of the Black Lives Matter movement, and I started reading about what was happening to Columbus statues across the country,” he said. “With removal of the monument off the table, I began exploring ways to use this monument as a vehicle for dialogue.”

Carlson sees the monument as a granite and bronze indignity, a symbol of worldwide transformations by Columbus’ voyage and of political domination in the country and city. The statue and station were built on what was originally tribal land and erased an entire Italian immigrant neighborhood. He considered several interventions, eventually settling on the idea of a community garden, focusing on indigenous crops.

“My goal was to create a venue for education of the space’s origin story and to bring people together for those important conversations,” he said.

Hannah Cameron, a Ph.D. candidate in urban studies and planning, took on one of the most notorious figures of European colonialism, King Leopold II. She established a dialogue between two statues of Leopold in Brussels and Kinshasa as a way to spark deeper conversations between the former colonial power and the former colony. Laura Brady, a master’s student in art history and archaeology, explored conflict over Skopje 2014, a massive urban design project that has created an ersatz capital city for the new nation of North Macedonia. She repurposed massive billboards to broadcast images of the majestic mountain sky—a symbolic rejection of the kitsch and consumerist city center. Architecture graduate student Chris Pearce tackled the haunting Moai statues of Easter Island, threatened by mass tourism and rising sea levels. He proposes a system of barrier islands that not only protects the statues, but also creates a living laboratory for ecological regeneration.

Lamprakos hopes that students learned not only to chart the lives of monuments, but also to creatively engage in discussions about historical memory.

“The monument is a kind of ‘flashpoint’ where repressed conflicts and traumas come together, bubbling up on the surface,” she said. “But recovering earlier layers of conflict and trauma may make it possible to come to terms with the past and find a way forward.