Over the past two years, schools across the United States have grappled with how to educate kids in the era of COVID-19. But, for a large subset of schools, the battle to provide a safe place to learn stretches beyond a global pandemic: Aging school infrastructure is compromising the health and safety of school communities across the country, particularly in underinvested, low-income communities of color.

Now, a pilot urban studies and planning course hopes to arm advocates with the critical data sources, tools and framework they need to lobby for school investment, cast a public spotlight on existing school conditions and fuel meaningful, lasting change. Led by Assistant Professor Ariel Bierbaum in partnership with University of Pennsylvania’s Assistant Professor Akira Drake Rodriguez, the course—and a resulting toolkit—seeks to position schools as critical community infrastructure integral to a community’s health, opportunity and resilience.

Focusing on the School District of Philadelphia (SDP), Maryland students recast techniques traditionally used in urban and community planning environments to create an online toolkit for guiding conversations and advocacy work around public-school building investment. Part story map, part strategy guide, the toolkit offers a 365-degree view of Philadelphia school conditions, illustrating how policies, funding and neighborhood conditions fed the cycle of school disinvestment. Using various state and city resources, students visualized the myriad problems facing schools at the city-scale, and walked through various strategies to harness, interpret and organize data. Together, it forms what students hope is a one-stop-shop for engaging advocates, communities and stakeholders in a constructive process for planning equitable public-school infrastructure.

“Managing school facilities isn’t traditionally treated as a community planning process,” says Bierbaum, who has been researching issues at the intersection of community planning and education for over 15 years. “School planning is not actually seen as a subfield of community planning. We don’t see courses on K12 schools in the graduate planning curriculum across the country. But why not? Public schools are public assets in our neighborhoods. Community planners can bring a lot to the table, especially in thinking about participation and engaging students and families in the process of designing and maintaining their school buildings.”

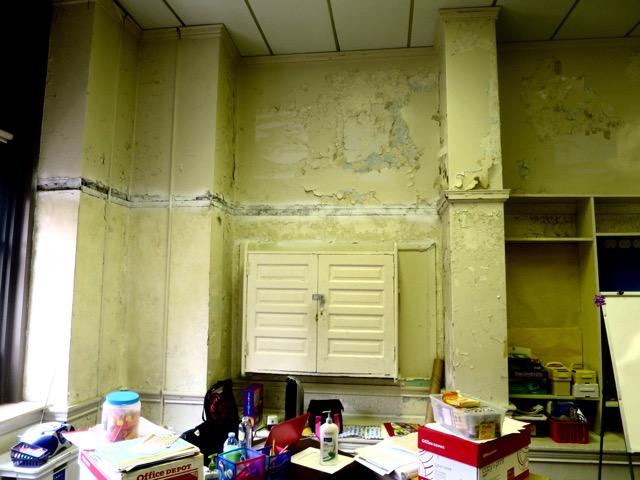

Unlike other forms of public infrastructure like roads and bridges, the federal government contributes zero dollars to school facility maintenance or management; state funding makes up a small fraction of the public-school infrastructure budget, with funding largely dependent on a local community’s wealth, leading to inequity across the country. A 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office report on school facilities found a gross percentage of schools—over half—with failing heating, ventilation or HVAC systems. In Philadelphia, the school system is currently has over $5 billion in deferred maintenance across the district. Across the city, teachers, staff and students navigate visibly crumbling buildings that hide the hidden dangers of asbestos, mold, lead paint and compromised drinking water.

“People, a lot of times, don’t know where to start,” said Jerry Roseman, director of environmental science and occupational safety and health for the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers Health & Welfare Fund. “The toolkit seems to be a natural answer. It would be useful to put in front of the city council to look and see what could be done with this kind of approach.”

In addition to providing regional context, interventions and an exhaustive roster of data sources, students pinpoint a number of strategies for leveraging that data for change; school district maintenance and capital needs data, for example, can help identify and prioritize schools ripe for investment. The students suggest that, by focusing on one school in each sub-area of the school district at a time, advocates can leverage that success story to infiltrate and improve other area schools. This bottom-to-top strategy is a great place to start, says Rodriguez, because it gives people hope.

“The idea is for each community to rally around a school in the neighborhood that has the most quantified problems,” said Winnie Cargill. “That would be a way to use the toolkit and to kickstart work in other schools in the neighborhood. It prevents people from saying, ‘the problem is too big.’”

The toolkit is grounded in the idea that community-based efforts are critical to moving school districts and city officials. “Pressure from the outside tends to be very good,” added graduate student Jeff DelMonico, who is currently a planning specialist for Howard County. “I do find that when we hear chatter, that gets around the conference room. It is that pressure, I think, that creates an avenue that didn’t exist before.”

Drs. Bierbaum and Rodriguez are building on the students’ toolkit in their ongoing action research with Philadelphia advocates as they develop a wide-scale People’s School Facilities Master Plan and planning process