For decades, the streets of Baltimore’s Broadway East neighborhood told the story of a community disappearing. Blocks of abandoned rowhouses illustrated the systemic disinvestment, growing crime and abject poverty tearing at the fabric of so many of Baltimore’s neighborhoods. But at a community meeting in 2016, Amber Wendland and her colleagues from design firm Ayers Saint Gross heard a different story: one of a once vibrant, tight-knit community; of church gatherings and afternoons on granite stoops; of thoroughfares lined with shops, a barber and a pharmacy. Said one lifelong resident, “Years ago, this used to be a village—and now the village is gone.”

Today, a new narrative is being written for Broadway East: rebuild the village. Leveraging existing assets, partnering with the neighborhood’s Southern Baptist Church, and elevating the voices of its people, the East Baltimore Revitalization Plan offers a path to a vibrant future that harkens to its rich past.

For Wendland, it manifests the power of community-driven planning and public-private investment; but it also epitomizes her work as a senior planner, leveraging dual backgrounds in design and community planning to realize the vision and voice of the communities she serves. While she has worked on several high-profile projects, from campus master plans to projects for the Smithsonian Institution, her passion lies in community-led projects in historically marginalized neighborhoods. Her personal investment in these places is obvious; she keeps close contact with stakeholders and closer tabs on each project’s progress, long after her role is complete.

“This is not rocket science,” said Wendland, reflecting on the vision for East Baltimore. “The things that communities in East Baltimore want are the same things that we’d expect in any community.”

The daughter of a landscape architect raised in the bucolic hamlet of Columbia, Maryland, Wendland was drawn to design early; a life-changing summer in Paris with the late Professor Emeritus Karl Du Puy during her undergraduate program at Maryland, was the “ah-ha moment” that would solidify her love for cities and lead her to choose a dual master’s program in architecture and urban and community planning.

“Maryland enabled me to marry the design components of the architecture program with the policy, process and engagement focus found in planning,” she said. “I can’t say enough great things about that experience.”

After graduation, she joined Ayers Saint Gross in Baltimore; while she engages in projects across the country, she relishes opportunities to apply her passion and skill to shape the city she now calls home. Her work earned her a spot in the Top 100 Women to Watch in Maryland by the Daily Record in 2021 as well as positions on the board of directors for the Neighborhood Design Center and the Baltimore Tree Trust. This year, she’s also back at UMD, teaching the next generation of planners and architects the tools they will need to find success in practice. Below, Wendland reflects on her work in East Baltimore, lessons learned from listening and the one attribute she strives to bring to every new project.

Community partnerships have become an integral part of your practice. Do you remember the first project that sold you on the idea of engaging deeply with communities? There were certainly experiences in school that shaped my interests and passions around community engagement, and I think that was solidified in my professional life. Equity and social justice are generations-long values in my family, but when I came to UMD, the planning program, especially, had such a focus on inclusion and elevating community voices.

When I landed at Ayers Saint Gross, I was fortunate that one of my first projects allowed me to leverage those values and passions. That project was the Southwest Neighborhood Plan, which focused on the smallest quadrant in Washington, D.C. This neighborhood was completely razed in the 1960s as part of urban renewal and rebuilt through “the Tower in the Landscape” style of development. When I came to that project, I thought, “Well, this is not great neighborhood design,” but the people who live there embrace the renewal style. It was a great opportunity and such a joy to be able to work with community members and have those frank conversations as we went through the process to figure out what the needs were and how we could integrate their diverse voices into the master plan.

The project eventually won an American Planning Association/DC Chapter project award. And it’s a framework that the city has used as they rethink equity and public housing in the Southwest quadrant, especially because of The Wharf and how that has completely changed the economics of Southwest.

Being a designer and a planner is a bit of a balancing act. How do you infuse a community with fresh ideas in design, great mobility, functionality and greenspace—all the things that people want and that you can bring to the table—and allow people who live there to reap the benefits? I think there are a few strategies. For the Southwest neighborhood, one of our big pushes was for the city to adopt a “build first” policy. The public housing was in really bad shape, so they were going to have to tear down and rebuild. But any development would require building first on a site so that no one was displaced—so that residents could move into that new development and not have to leave their community.

Too often in development we see complete gentrification and displacement, which frankly is what has happened in many neighborhoods across the District. Even if residents are temporarily displaced, by the time affordable units are built they have already resettled in another community and often don’t come back. That’s what we’re trying to avoid.

In the case of Baltimore, homeownership is not just important because it plays a role in people’s attachment to their community; it is also critical to building community wealth.

The other piece that was really important in our East Baltimore project was ensuring not just a range in affordability of the units, but also a range of unit types. In East Baltimore, 95% of the housing stock are rowhomes. If you have a homogeneous housing stock, you’re going end up with an economically homogeneous population. One of our priorities was identifying a corridor where there was significant vacant land and opportunities to introduce different housing typologies and overlay affordability without displacement. We want people to be able to age in place. A young, single adult may move into the neighborhood but eventually need a bigger place when they start a family, or an older couple may want to downsize but remain in their neighborhood—and all those things need to be accounted for.

You were the project manager for the East Baltimore Revitalization Plan, which began shortly after the unrest over the death of Freddie Gray. What challenges did you face at the project’s start and how is it going today? In many parts of Baltimore, there’s a legacy of mistrust, broken promises and racist policy. All these elements, over time, add up. So, starting a process that was purely focused on listening and trust was fundamental to the success of the project. It was all about elevating the community’s voices and building the relationships to support those ideas, not prescribing what we thought should happen.

This is not rocket science. The things that communities in East Baltimore want are the same things that we’d expect in any community. Figuring out how to restore the village that existed years ago was the mission of that project. Our client, the Southern Baptist Church, is currently moving forward on a new health and wellness center, new mixed income housing, park and streetscape improvements, and more. But it hasn’t been easy. These projects can take two or three decades to fully realize. One thing that projects need is a champion, and we found one in Bishop Donte Hickman, the Senior Pastor at Southern Baptist Church. He has been a powerhouse throughout the whole process, and he does what it takes. He has great vision and is driven to rebuild the village surrounding his church. A leader like him is critical for projects like this.

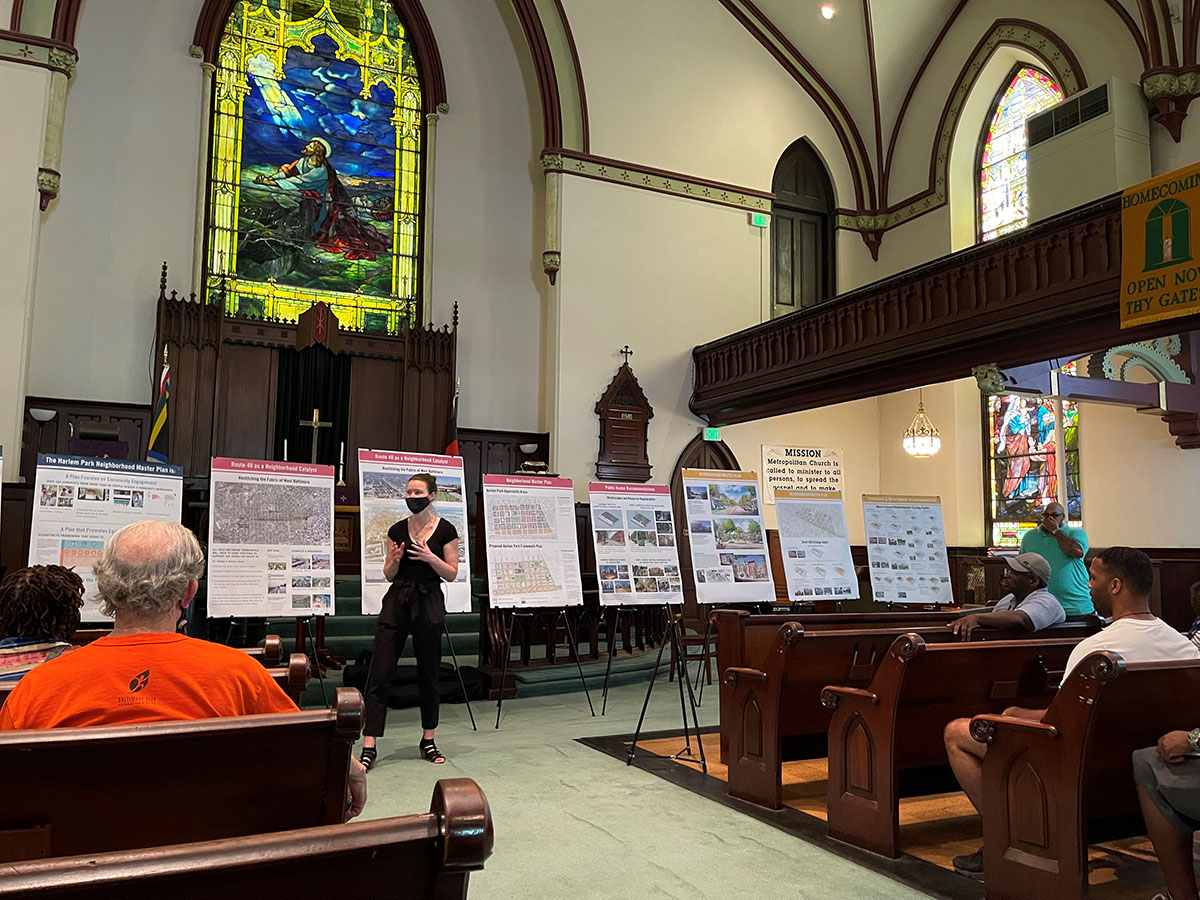

There are many planning and design-related factors that, in essence, are social and economic determinants of neighborhood resilience. In your work with communities, have there been any that have surprised you? For our work in Harlem Park, we issued a community survey and one of the questions asked about access: What’s the biggest impediment to getting from point A to point B? Harlem Park is comprised almost entirely of housing and churches, so people have to leave the neighborhood to get even their basic needs, like groceries or a doctor’s visit. I thought the predominant answer would be reliable transportation, but I was wrong. The number-one answer was the quality of the public realm—the fact that people are walking past trash and crumbling sidewalks, vacant housing and unmaintained streetscapes. That is the biggest deterrent for accessibility: basic public infrastructure and maintenance. I appreciate progressive, thoughtful design, but in many of these communities, we’re just talking about really basic design elements. Elements like good lighting and nice streetscapes, those are all components of a resilient community.

What’s a project, big or small, that holds special meaning to you? Well, East Baltimore is my heart. But my work in Harlem Park was also an incredible project. Tragically, our client there, Matthew King, who was the director of the Harlem Park Community Development Corporation, passed away shortly after we finished the planning effort, and he was such a champion of the work. I love that work and am very proud of that plan but it’s uncertain what will happen next. It will take someone in the community willing to take up that mantle and move it forward.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received? It’s such a tough question. I think mine is less of a quote and more a personal value that is important to keep in mind when designing and working with communities, and that’s humility. I think designers—because of education and our experiences—often fall into this trap of thinking we know the best solution. When you’re working in communities with people who have been there their whole lives, many times you need to set those assumptions aside and embrace your humility and really truly listen.

What’s next? I’m excited to be working on a master plan for a non-profit camp, and there’s another community-based planning project in Alabama, similar to the East Baltimore project, that I’m championing. I’m also working at Coppin State University on their campus plan—its an incredible campus and I’m excited about their future. I enjoy my work at the Neighborhood Design Center where I serve on the board—talk about aligning with my personal values! It’s been such a joy to be part of that organization. And I’ll be back teaching an urban design software course at Maryland this summer. I remember finishing my first class over the winter semester; it was 9:30pm, I’d had a full day of work and yet I was so full of energy. I had forgotten how much I love teaching and I’m excited to keep passing on the lessons learned in my professional life down to the next generations!