Isabel Anderson sits in a quiet corner of the Architecture Building, spiral-bound notebooks spread neatly across her desk. Working quickly with her pencil, Anderson is telling a story: not through words and phrases, but one that’s carefully constructed with walls and windows.

Anderson's project is part of a design studio course, one of two this semester that are teaching students how perception, daylight and movement can create a compelling narrative that—like a good book—transports users on an inspirational, dramatic, even whimsical journey.

“Architecture can be a really powerful tool for telling a story, whether its about the space’s programming, its surroundings, or just to make a statement,” says Assistant Clinical Professor Brittany Williams. “Our students are exploring how they can enhance a user’s experience by playing with the building’s physical aspects.”

Both studios, ARCH402 taught by Williams and co-instructors Lindsey May, Eric Hurtt, Joshua Hill, Daniel Curry and Vyt Gureckas, and ARCH 405, taught by Julie Gabrielli and Marques King, have doubled down on the storytelling concept by challenging students to design a space for actual storytelling—spoken word performances like poetry slams, book readings, and MOTH-type storytelling sessions. Key to each student’s design—and a critical tool for their growing design toolbelt—is the successful development of an architectural promenade, where a sequence of spaces and other physical elements create an experiential journey through the building.

“We encourage the students to consider how people will engage with each aspect of the building,” said Williams. “What’s the experience on the street? How will they navigate from the lobby to the performance space? How can the architecture prepare people for the activities happening in the building—in this case, storytelling—and enhance the experience?”

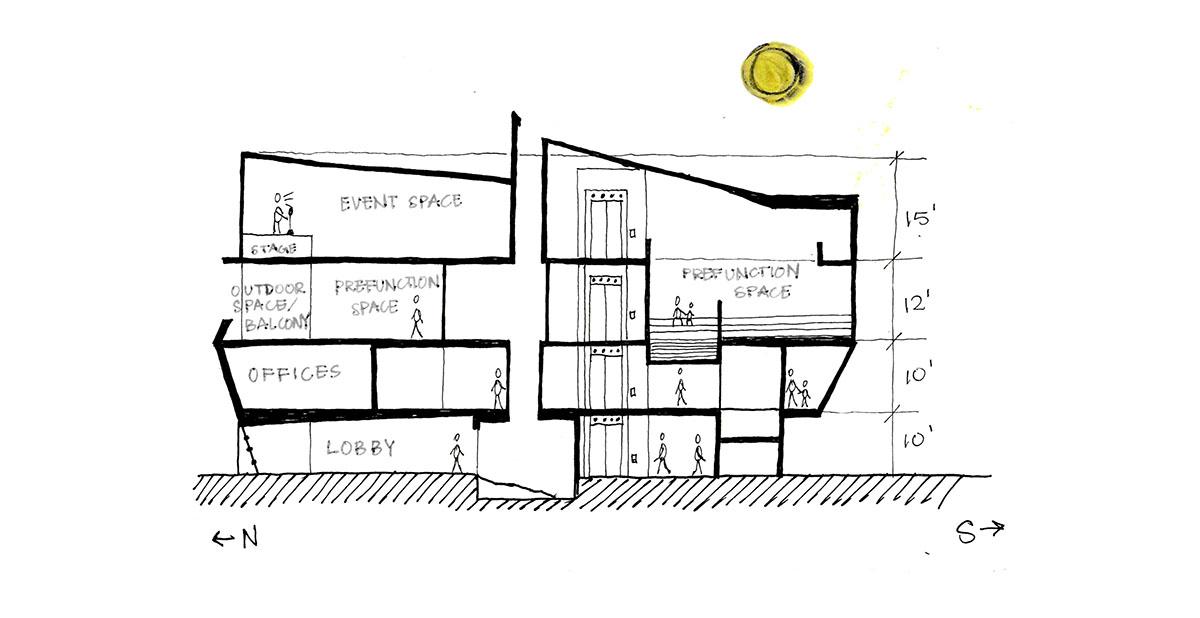

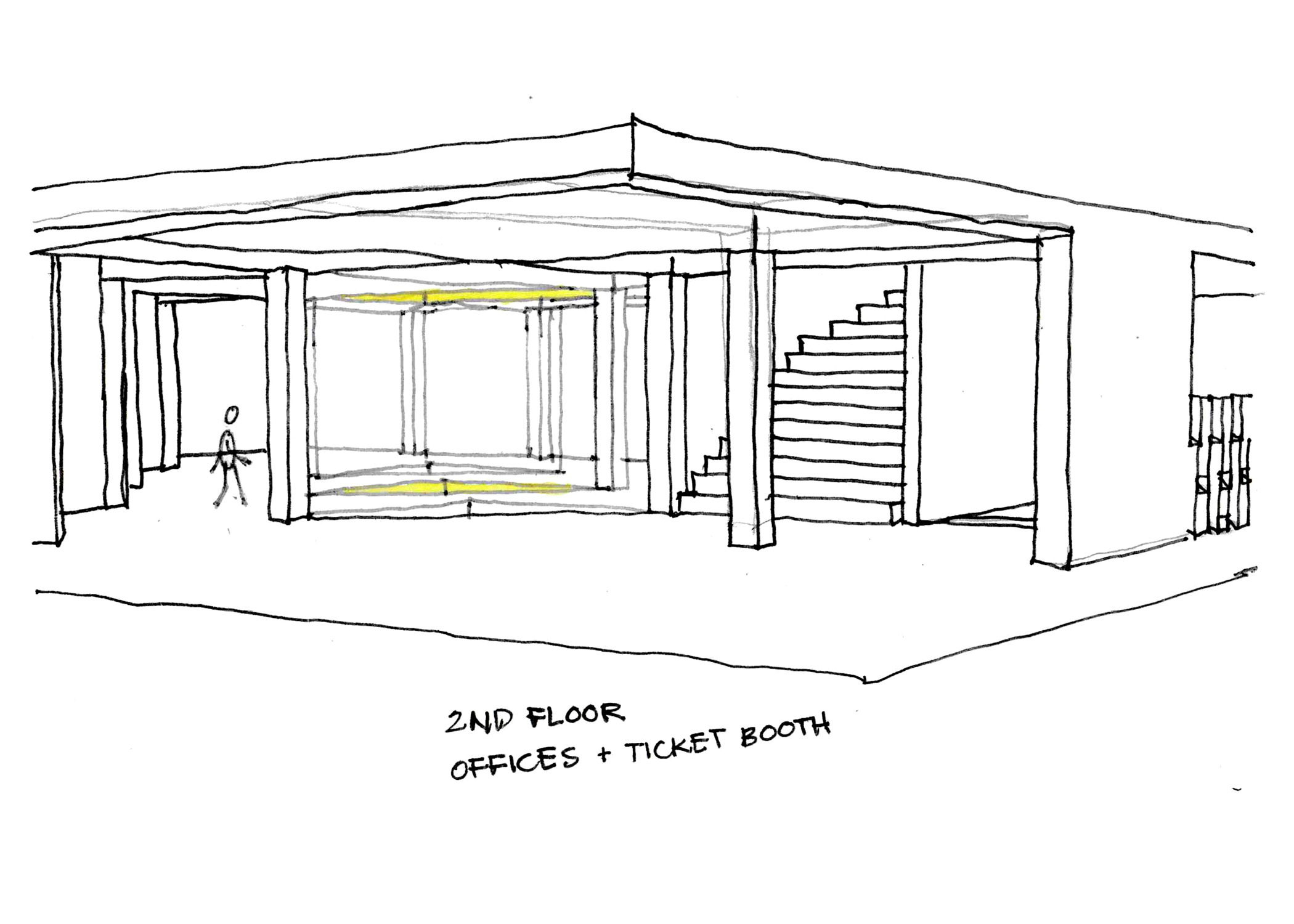

Architecture undergrad Wisdom Harden is using light as a tool to connect different sections of her building and guide circulation. Light wells create the effect of compressing and expanding space from floor to floor, while elements like angled walls and geometric furniture direct people, revolving them upward through different levels, spaces and experiences.

“In my mind, when you tell a story, it’s supposed to be linear and it’s supposed to make sense, but there is some bouncing around that happens,” she said. “I tried to create that playfulness through light and shapes. Looking at precedents, I saw how architects leverage furniture as a directional tool and for wayfinding, but it can also be something people can use, encouraging folks to interact with each other in different ways.”

While ARCH 402 students are tackling a hypothetical site in Washington, D.C., ARCH 405 centers on a real space in the Baltimore enclave of Mount Vernon, a long, narrow building sandwiched next to the site of a beloved local bookstore, since closed. The site offers some limitations to the students but also opportunities; students have spent the past few weeks testing out ideas through multiple iterations.

"To connect concepts like narrative and promenade to the specifics of architectural language, the ARCH405 students are studying the relationship between ideas, structure and space,” said Gabrielli. “One particularly effective tool is to work in section using diagrams, hand drawings and models."

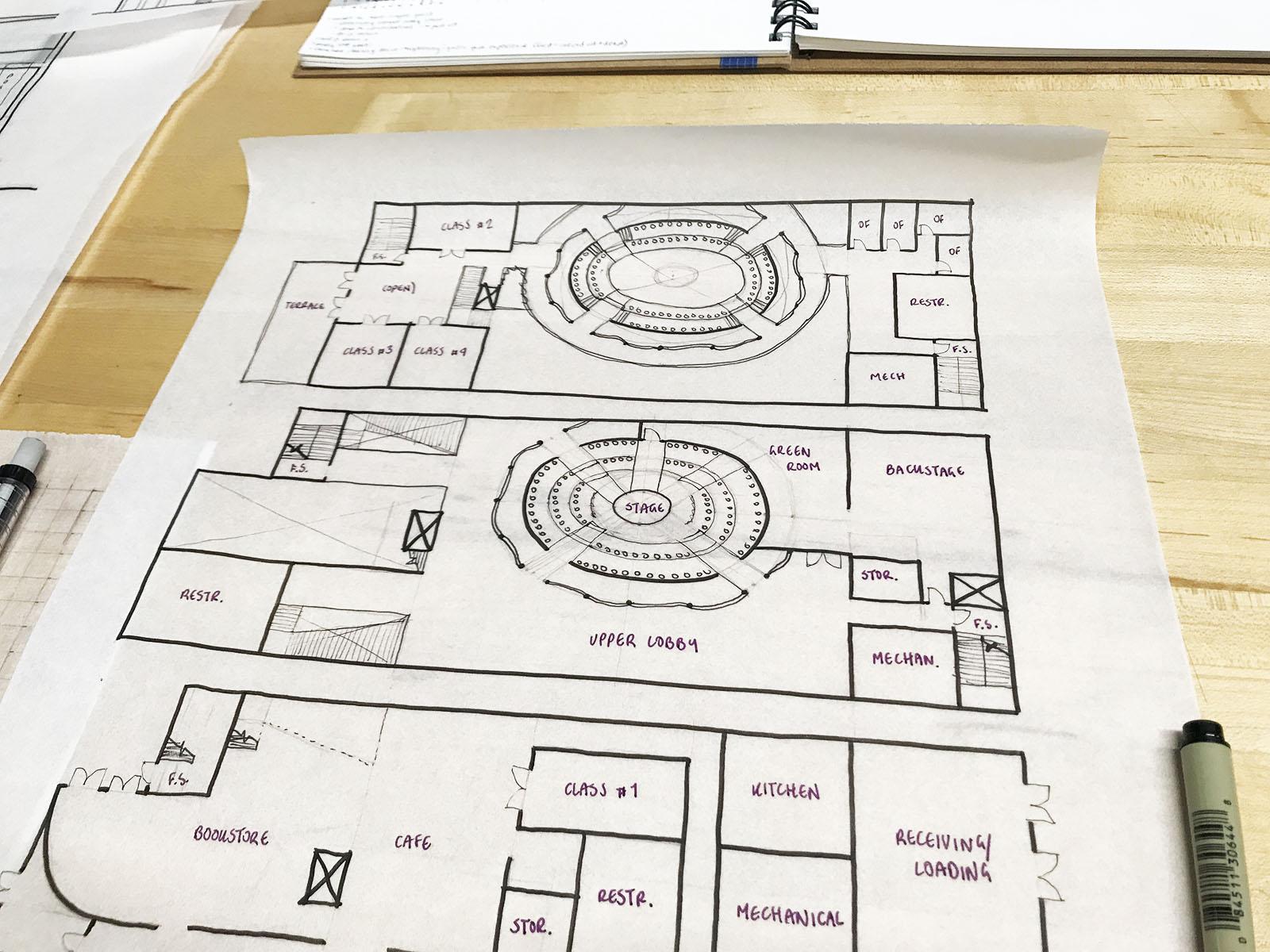

Anderson, a huge fan of spoken word performance, is taking some inspiration for her design from a Sarah Kay poem: “Maybe I’m learning the art of capture, maybe I’m learning the art of embracing, maybe I’m learning the art of letting go.” Anderson’s concept embodies that phrase through three distinct spaces in her building: a compressed lobby that captures the visitor from the outside urban expanse; a circular auditorium that embraces a center performance space, where performers “give” their story to others; and a third-floor outdoor garden terrace, which connects visitors to the outside world before they leave.

“The garden helps finalize that process,” she said. “It’s meant to be the universe reclaiming the story—you’re letting go and giving it back. I try to draw everything with that in mind.”

Students are now working to maintain their vision while adding the nuts and bolts of a functional building, which include key features like bathrooms, staircases and utility rooms. Striking that balance, says Hurtt, might be the most challenging part for students, but critical for delivering a functional space that also inspires.

“We are encouraging them not to lose that focus on the experience,” said Hurtt. “But you’ve got to make the ideal real.”