One of Washington, D.C.’s fastest-growing hot spots may be a recreational and culinary boon for D.C.’s human inhabitants—but it’s a bummer for its winged ones, particularly the reclusive American bittern, a native bird that makes its home along the Anacostia.

So when undergraduate architecture student Valeria Lopez conceived a proposed residential enclave for Navy Yard, the Southeast D.C. neighborhood known for Nationals Park, she considered both District denizens and wharf-frequenting waterfowl. Her scheme, which features a staggered cluster of mixed-use buildings, buffers its waterfront views with expansive green space and a robust constructed wetland, transitioning from an urban vibe to an organic one.

It’s just what architecture Lecturer Sarah Bolivar had in mind for “Animal Occupation,” a new summer studio course that explored the co-habitation of humans and wildlife at the intersection of built and natural environments. Using five distinct ecosystems along the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, students were asked to design for dense, highly populated areas—from Miami Beach to Maine—each with special consideration of an indigenous species that bears the brunt of human activity.

[Architecture Student Designs Imagine an Autonomous Aerial Future]

“These coastal areas are prime real estate and often heavily developed,” said Bolivar, a landscape architect. “I wanted to challenge students to think about how animals, who have called these places home long before humans, fit into this new urban ecology. How do we encourage more hybrid spaces despite these constraints?”

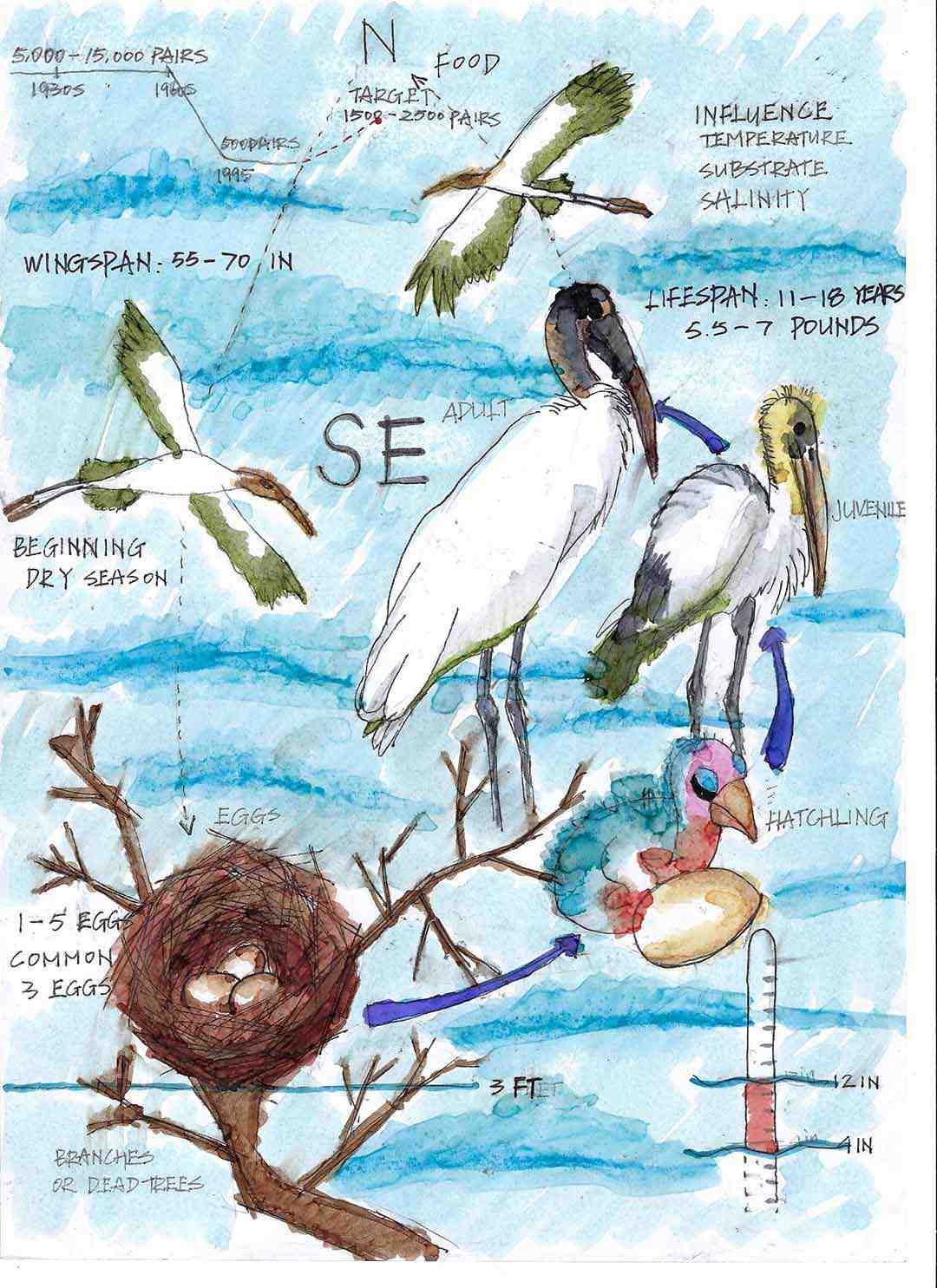

Students spent the beginning of the nine-week summer course researching their sites and the animals they intended to protect, along with both architectural and landscape precedents. Then they created sketches and experimented with physical models to test ideas that both connect and separate wild and urban areas with design interventions such as strategic placement of communal spaces and thoroughfares that guide human movement.

In Myrtle Beach, S.C., students considered the loggerhead sea turtle, an essential player in the marine ecosystem whose migration from dune nests to the sea is often fraught.

“Baby turtles are easily distracted and particularly vulnerable to human activity,” said Xuan Vo ’24, who elevated her proposed hotel 11 feet, creating both a safe spot for turtle nesting and an engaging observation area for guests. “One of the biggest challenges for them is artificial lighting, which sends them inland rather than out to sea.”

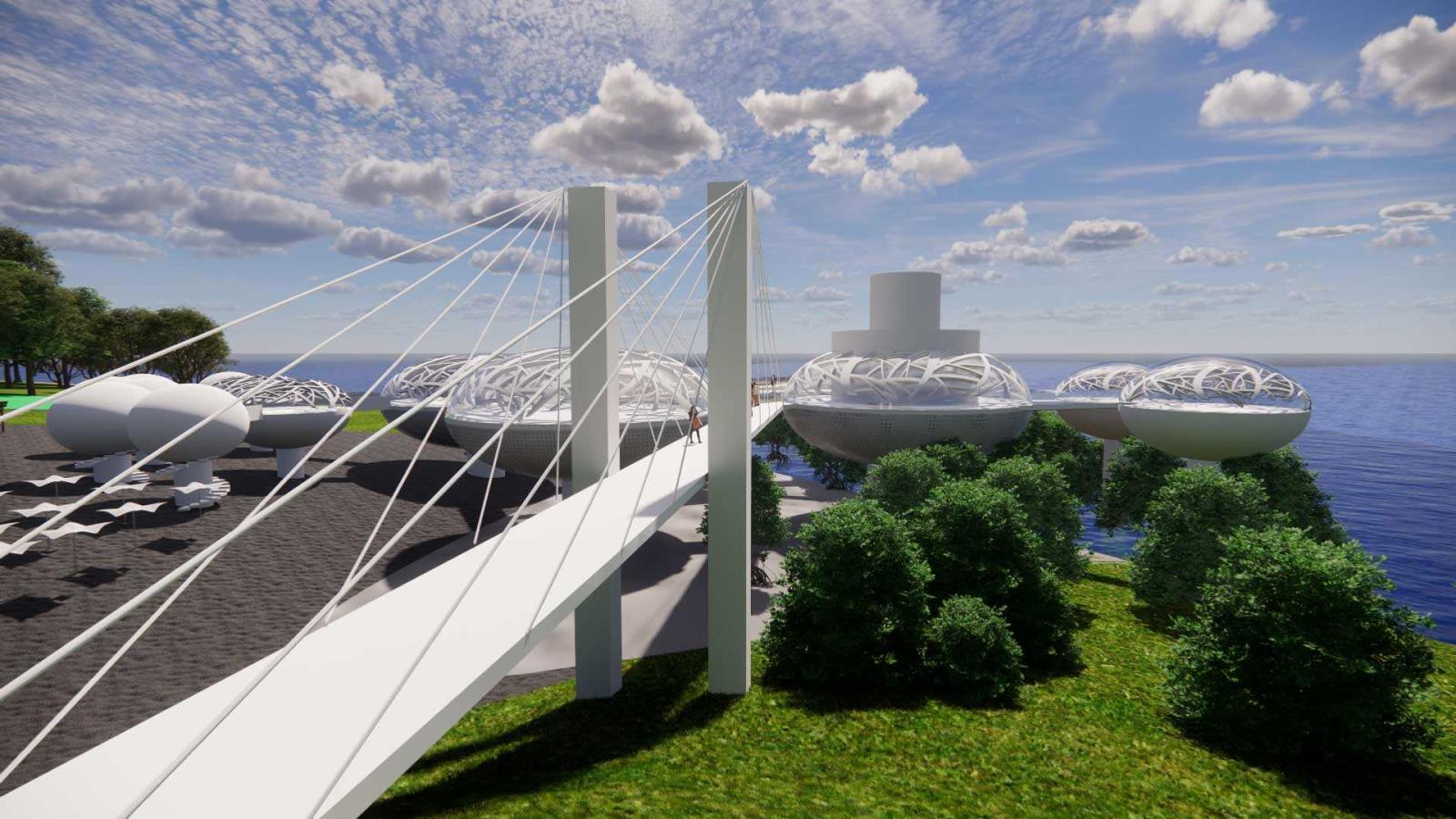

A proposal for New York City’s coastal Sunset Park replaced an old pier in Brooklyn with five elevated “public education” jetties. The jetties featured pedestrian pathways and greenspace built atop a marine animal education and monitoring center, with direct sightlines to secure resting areas for Horseshoe crabs underneath. A design for Portland, Maine, would reposition a popular trail out over the ocean and create an intertidal area that closely connects Maine’s outdoorsy population to its lobster habitats.

Animal research on habitat, behavior and personality—reflected here in Dunkerson's art—offer cues for resilient designs that serve both humans and animals.

The students also sought inspiration for their designs from the animals’ habitats and life cycles; Lopez’s Navy Yard plan made use of native materials often seen in bitterns’ nesting areas, while residential building designs for a wood stork habitat in Miami Beach, Fla., resembled spherical nests, elevated to commune humans with their winged neighbors.

“Strategies that contribute to resiliency of place for humans while offering compatibility—even enhancement—of habitats for these special animals, these kind of design solutions solve multiple problems at once,” said Clinical Associate Professor Julie Gabrielli, one of the guest critics.

In an increasingly volatile climate, architects can promote ecological preservation by bringing holistic, resilient solutions to the table for clients, said reviewer and architect Jack Cochran.

“Your future clients are probably not going to be asking you to think about wildlife,” he said to the students. “But we have a responsibility not just to them but to the wellness and health of the environment.”

The studio’s value goes beyond multispecies design, said guest critic and landscape architect Rebekah Armstrong, in that it will help young architects get into the mindset of the client—whether they have two legs or four.

“You may not be designing for storks or sea turtles in the future, but adapting someone else’s point of view is something you’ll be doing all the time in design,” she said.