A single sliver of ceramic might not reveal much about the Virginia plantation where it was discovered. But amass thousands of them in a room and a story begins to take shape—told through Chinese porcelain teacups and punch bowls, earthenware chargers and shaving basins.

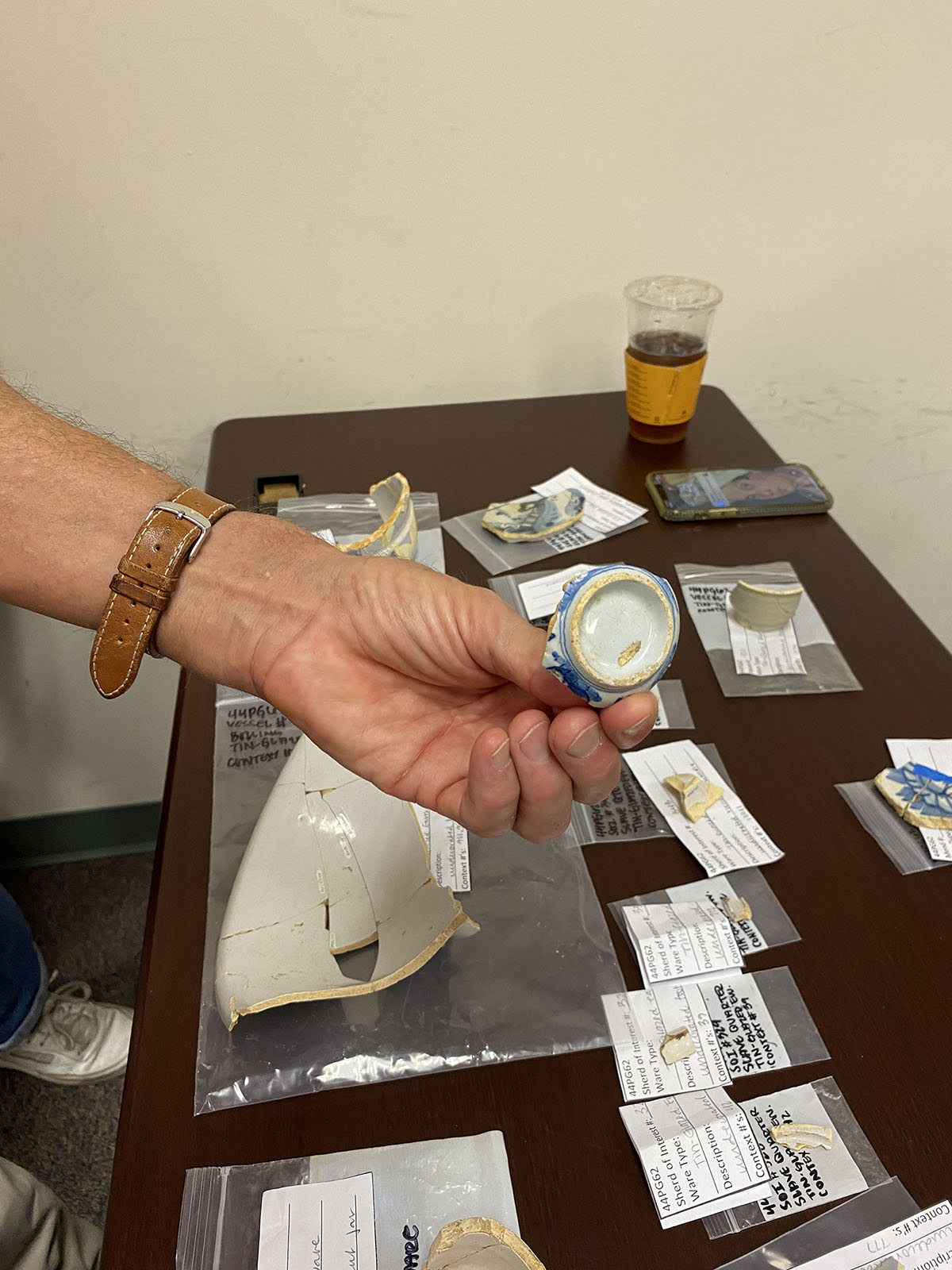

Fragments of 900 individual ceramic “vessels” and another 600 sherds of interest excavated from Virginia’s historic Kippax Plantation were put on view last week by students and faculty from Maryland’s Historic Preservation Archaeology Lab for additional analysis by two national ceramics experts to further construct the people, place and activities of one of early America’s frontier trading plantations. Lining over a dozen tables in a conference room deep within Preinkert Hall, it’s the first time such a large portion of Kippax’s artifact collection—which numbers several hundred thousand sherds—has been laid out for examination at one time.

“You can imagine how a room would look with 1,500 intact pieces; it would look like a rummage sale,” said Rob Hunter, former curator of ceramics at Colonial Williamsburg and founding editor of Ceramics in America. “This is a luxury to have this kind of space–and you need it to make these associations.”

Among the many artifacts found on the property, ceramics offer critical clues to the lived history of Kippax: the size of families who inhabited the plantation over the centuries; the number of enslaved on the property; their interactions with Native Americans; even how often they entertained. Hunter and ceramic specialist Leslie Bouterie stood shoulder-to-shoulder with students over rows of colonoware, creamware and other ware types to offer insight on the pieces’ origin and utility, to identify the unknown and flesh out the plantation’s timeline.

This is a great example of archaeology working,” said Historic Preservation Postdoctoral Associate Stefan Woehlke. “And we have a historical record that adds to what the material record is showing.”

Located on the southern banks of the Appomattox River, Kippax Plantation was the 17th-century home of English merchant Robert Bolling and Jane Rolfe, the granddaughter of Pocahontas. Kippax has been an active archaeological research site since 1981; initial excavations were carried out by Professor Don Linebaugh and Rob Hunter, then fellow graduate students at the College of William and Mary. Work at the site has unearthed multiple 17th- and 18th-century structures and thousands of artifacts that shed light on the trade history between Native Americans and early European settlers, as well as the lived experience of the enslaved African American slaves who worked the plantation for nearly 200 years. Kippax has been an ongoing project for Maryland’s Historic Preservation Program since 2004 and has introduced the processes and techniques of archaeological preservation to dozens of graduate students.

“Crowdsourcing” with colleagues who have seen a variety of sites and materials, says Linebaugh, helps him and his students not only with identification of artifacts, but interpretation. A set of beer mugs from the early 18th century suggests the plantation’s status as a popular outpost for traders and frontiersmen as they traveled south and west. Other objects provide a timestamp of sorts; the presence and absence of certain types of ceramics, often identified by color or pattern, helps solidify the chronology of plantation activities and determine who is living on the plantation during different time periods.

“The material record adds a tremendous amount of depth and color, and really this human connection that’s just so great,” he said.

Brightly colored, English-made transfer-printed pottery that was excavated at the slave quarter’s site is a stark contrast to the everyday undecorated colonoware made and used by Black and Indigenous communities; it would have been considered a very special acquisition, says Bouterie, who has studied transfer printed wares for decades as a visiting curator and volunteer at estates including Montpelier, Monticello and Lincoln’s Cottage.

“It tells you that they are using their limited funds to purchase objects of beauty,” she said. “This choice—the colors, the patterns—is an expression of their individuality.”

Linebaugh hopes to share pieces from the Kippax collection with other regional experts in the coming year, including an upcoming trip to Colonial Williamsburg to consult with archaeologists working on their colonoware collection. The lab also received a grant to conduct a materials analysis on Kippax’s colonoware collection and their provenance, confirming which pieces were made by Native American hands and which by African Americans.

“Don’s done an amazing thing here—not only the continuity of telling this important story, but the dedication to keep it going and share it,” said Hunter. “The coolest thing about this stuff is that, once upon a time, it was trash—but now it’s being used to instruct young minds about the past. Every piece is a time machine.”