Pictured above: Henry Randall's was the first home built in North Brentwood in the 1890's and burned down in the 1990's. The home for Henry's son Peter was the second home built in North Brentwood, also in the 1890's and can be seen at right.

The overgrown lot in the small town of North Brentwood, Md. is easy to miss for the thousands of commuters who pass it daily on Rhode Island Avenue heading to and from Washington, D.C. But just under its weedy surface lies a remarkable story waiting to be unearthed—one told through amber glass and 19th century nails, peculiar metal and old coins.

With each shovel of dirt, students from the University of Maryland are hoping to piece together a chronicle of the Henry Randall House, the first residence built in one of the state’s oldest Black incorporated towns, and with it, capture more than a century of daily life marked by emancipation, Jim Crow and the civil rights movement.

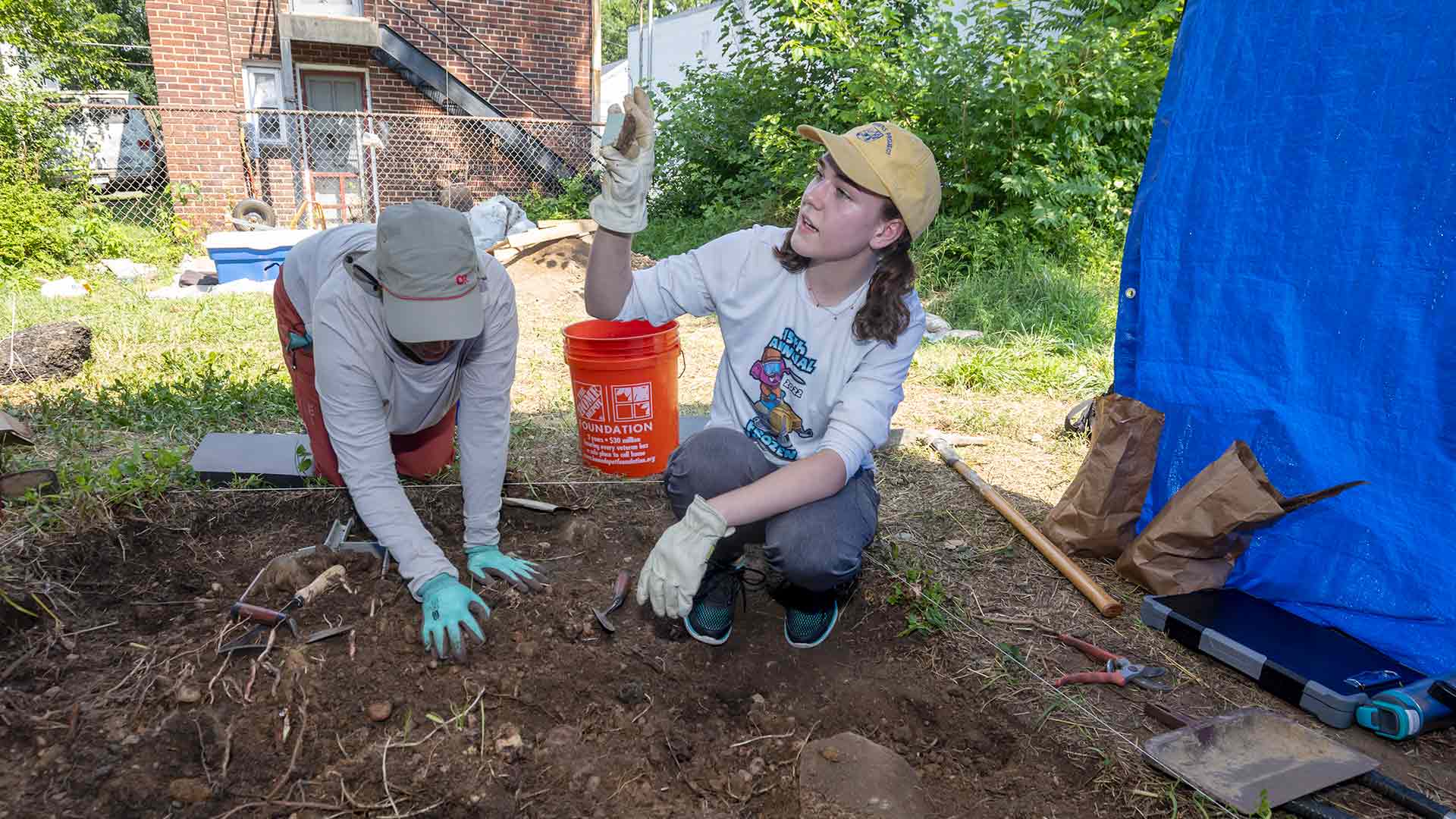

Armed with trowels and sifters, students in a summer archeological field school taught by Historic Preservation Postdoctoral Associate Stefan Woehlke Ph.D. ’20 are spending the next four weeks meticulously navigating tangles of tree roots, rocks and decades of compacted dirt to reconstruct the house’s history. Working within three-foot squares, students carefully peel back inches of soil at a time, a layering method that allows them to recover evidence from different eras, rolling back the clock the farther down they dig.

“We have to be really careful,” said Emily Lucie ’23. “If we were just to rip up a root, depending on how deep it goes, it could then pull soil up from lower layers and potentially pull up tiny artifacts with it, which contaminates the timeline.”

The smashed cans, Metro tokens, even jewelry that they find—collectively called diagnostic artifacts— link the layers to time periods discerned by the manufacturing technology used. So, pieces of window glass and a door hinge will help students date the original structure and any later additions to the house, while a pull tab lodged in a layer of asphalt can determine when the driveway was added. Artifacts also offer clues into the activities and behavior of residents: A Danish coin students recovered several inches below the surface hints to possible travel abroad. Compiled with deed records and other historical information, found objects can connect the site to family lines, offer a snapshot into their daily life, and determine how the property changed over time.

“Increasingly, we’re applying archaeological thinking to current-day questions, such as the impact of segregation and disinvestment in Black communities,” Woehlke said. “These physical artifacts connect us with the people who lived in these communities and better understand their experiences.”

Henry Randall and his extended family first populated North Brentwood—originally called Randallstown—in the late 1800s, purchasing land from Capt. Wallace Bartlett, a white Army commander who led a regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. Randall built the multistory wood-frame farmhouse in 1892; the town doctor purchased the property, where he lived and saw patients, in the mid-20th century. The town was renamed North Brentwood in 1924; it was the first municipality in Maryland without any white voters. Despite its flood-prone location along the Anacostia River, North Brentwood was a thriving sanctuary for African Americans in a segregated America. Barred from patronizing white-owned businesses, North Brentwood residents established their own; Randall himself ran a company delivering coal and ice.

The Henry Randall house changed hands several times before it was damaged by a fire in 1994. Woehlke suspects that the remains were simply demolished, shoveled into the basement and covered with topsoil. The students centered one of their digs in the area they suspect the basement is located, guided by abrupt changes in soil, a pattern of asphalt and town records. A foundation wall was unearthed within a few days.

“It’s like magic,” said Woehlke. “I’ve done this so many times, and every time I wonder, ‘Is this really going to work?’ But it does—and what we find helps tell the people’s history.”

The excavation is one of several projects underway between UMD’s Historic Preservation Program and North Brentwood to preserve the heritage of several town landmarks—including the iconic Sis’ Tavern, a jazz haunt of Duke Ellington during segregation, and the Windom Road Barrier, a dilapidated metal guardrail erected in the 1950s to physically separate North Brentwood from its white neighbors.

“It’s easy to walk by this and see an abandoned lot, but this project transforms it into a really interesting story, how North Brentwood came to be and that it existed because of segregation,” said Henry “Quint” Gregory, director of UMD’s Michelle Smith Collaboratory for Visual Culture. “It’s so important for those stories to be told and to be known.”

The materials collected will be taken back to campus to be cleaned, cataloged, analyzed and eventually added to the town’s growing digital history project. As for the site, the town has planned to transform the lot into a park celebrating a century of Black entrepreneurs, beginning with its founding resident.

“It’s an amazing discovery,” said Dame. “Hundreds of people pass through our town every day and don’t know our history. Our effort now is to have them discover it.”