This story appeared in Maryland Today

It’s hard to imagine that the raucous activity (and raging traffic) of Washington, D.C.’s Dupont Circle could be rivaled by what’s happening just under its sidewalks. But what was once the city’s first underground trolley station (and later, a much-maligned food court) now thrums with large-scale sound and light projections, night markets, performances and art exhibitions.

“Dupont Underground: Layered History and Possible Futures,” which opens this evening at the University of Maryland’s Kibel Gallery, tells the history and evolution of Dupont Circle, and how the abandoned rail stop was transformed into a popular platform for D.C.’s thriving art scene by a team of architects, planners and other city stakeholders, including two UMD alums.

“The idea was to essentially give a public space over to the public and let them do stuff in interesting ways,” said Alick Dearie ’99, M.A. ‘04, who was an early architect on Dupont Underground and is now chair of its board of directors. “The cool thing about a space being found—and in a lot of ways elevated by the architecture—is we see the beauty of what it is but also the possibility.”

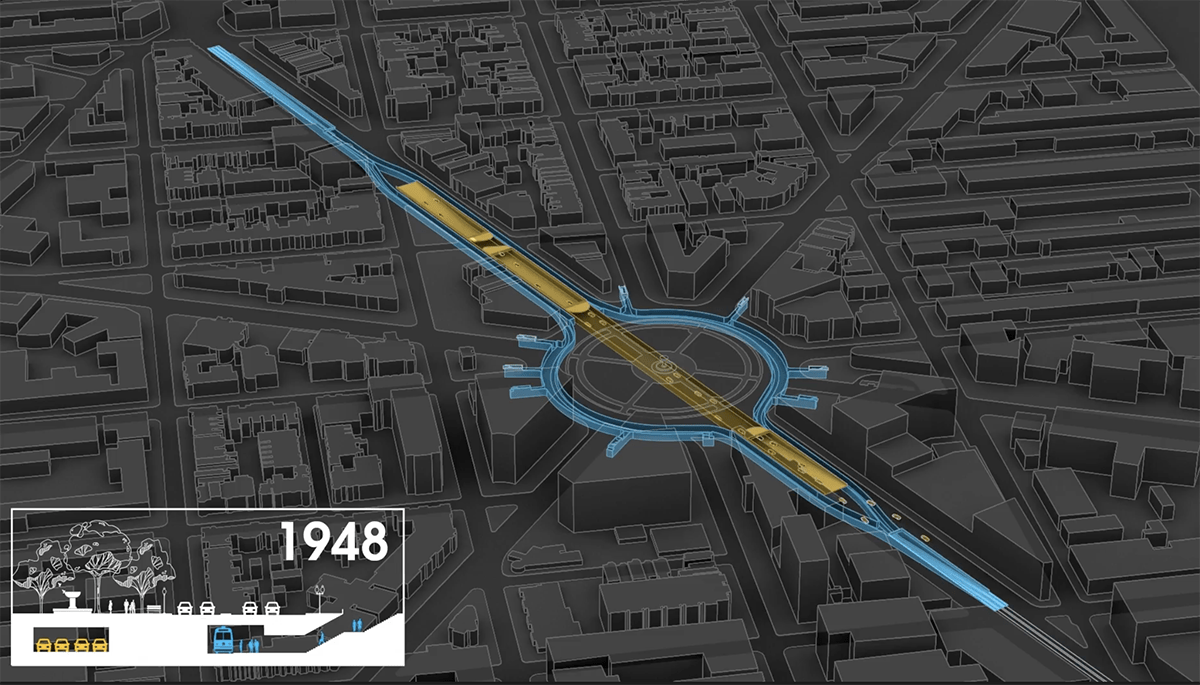

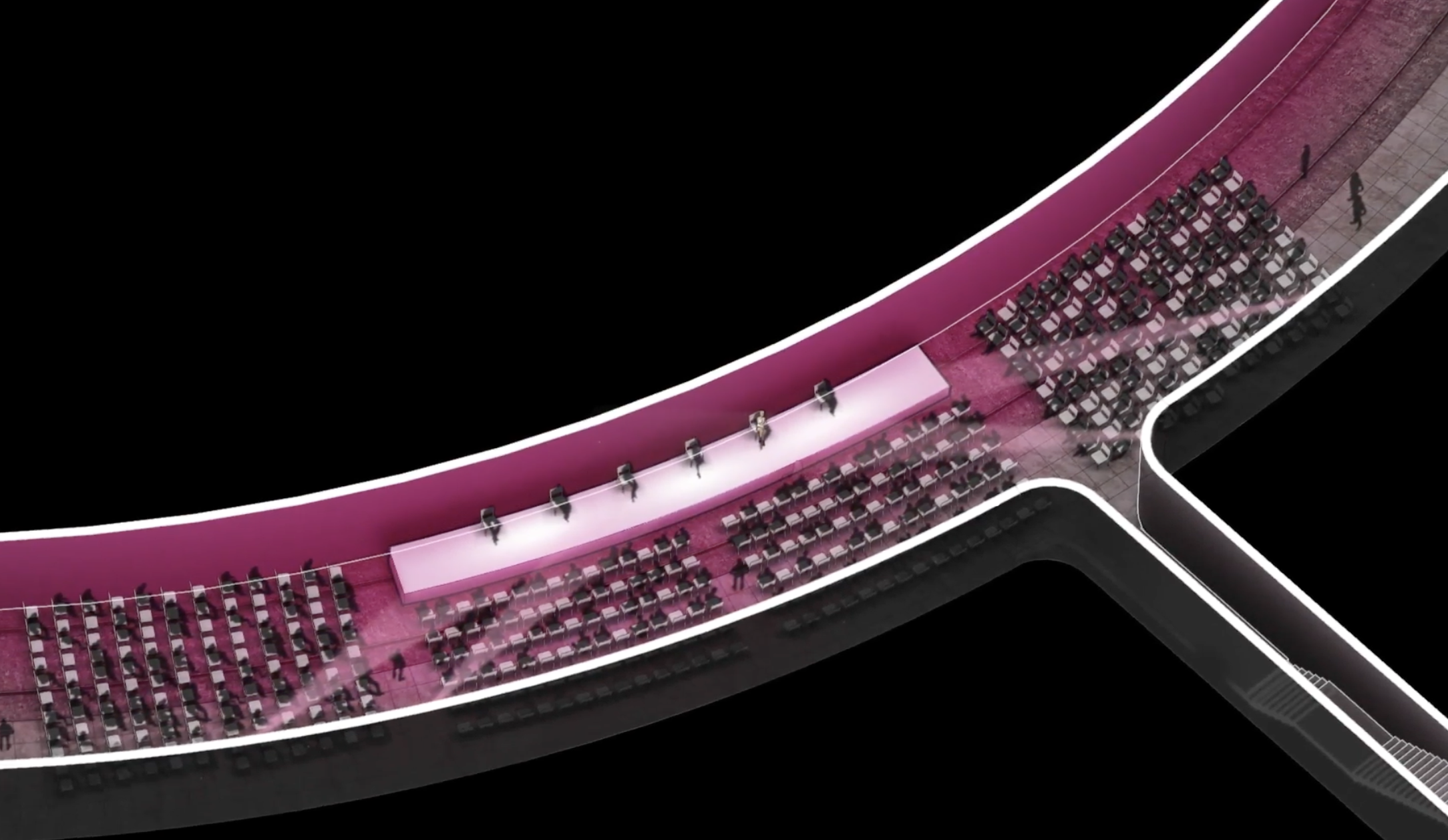

Featuring a commissioned animation by architect Jack Solomon that draws on archival photographs, drawings and documents, the exhibit takes visitors on a shape-shifting odyssey of Dupont Circle, rolling through a century of changes in the urban landscape, how people moved and the impacts below ground.

“There have been many chapters in the life of this space that have been very specific, and maybe that hasn’t worked out,” said Clinical Assistant Professor of architecture Lindsey May, who directs the Kibel Gallery. “This project shows the promise of doing things differently.”

The Dupont Circle trolley station was constructed in 1947 (along with the Connecticut Avenue vehicle underpass) to bypass Dupont’s notoriously clogged rotary, a busy thoroughfare for visitors and residents heading downtown, to nearby Embassy Row or the capital’s northwest suburbs. America’s auto boom, repeated labor strikes and the promise of D.C.’s Metrorail shuttered the streetcar line in 1962. The station’s east and west underground platforms served as a Cold War-era fallout shelter during the 1970s; in 1995, the west platform was transformed into a poorly conceived food court, doomed by poor ventilation, a worker shortage and financial mismanagement. Called Dupont Down Under, it lasted just three months, leaving behind remnants of its fast-food tenants and plunging the tunnels into darkness and disrepair.

When the city issued a request for proposals to resurrect the dormant space in 2010, only one group answered the call: Hunt Laudi, a design studio helmed by architects Julian Hunt and Lucrecia Laudi. Envisioning a transformation similar to New York City’s High Line, which turned a 1.5-mile elevated train track into an art-infused linear park and tourist magnet, they brought in restorationists, preservationists, planners and architects, including Dearie and Brian Grieb ’99, M.A. ‘04 of GriD Architects. While the site underwent an extensive cleanup, the team eschewed a full commercial effort, instead showcasing the historic qualities that makes the underground space unique.

“It’s a unique story that demonstrates how, as professionals in different facets of the built environment, we work better together,” said May. “The success of cities specifically requires collaboration and buy-in from all these different disciplines.”

Since 2016, emerging and experimental artists have all found a place among the bare concrete and well-worn tracks, which were kept intact. Dupont Underground’s first show, “Re-ball,” repurposed the 650,000 plastic orbs from the National Building Museum’s “Beach” exhibition into a towering, traversable landscape. Its latest show offers a series of intimately constructed living rooms, each designed by a D.C.-based architecture firm, where visitors can sit and take in Swedish short films. Dupont Underground has built partnerships with the Kennedy Center, Washington Opera, embassies and other institutions seeking an unconventional space.

What’s next for Dupont Underground, said Dearie, is a frequent topic of discussion among stakeholders; the art and culture institution only occupies a small portion of the former platforms, and there is potential to work with the city to program an additional 45,000 square feet. Like its history, the underground relic continues to evolve.

“This isn’t a story about a beautiful project that was easy to get done,” said May. “It’s a story about something that has slowly built and developed over time—and is still under construction.”